Origin: A Beginner’s Guide to Deep Reinforcement Learning

Introduction

Deep reinforcement learning combines artificial neural networks with a reinforcement learning architecture that enables software-defined agents to learn the best actions possible in virtual environment in order to attain their goals.

That is, it unites function approximation and target optimization, mapping state-action pairs to expected rewards.

Reinforcement learning refers to goal-oriented algorithms, which learn how to attain a complex objective (goal) or how to maximize along a particular dimension over many steps.

RL algorithms can start from a blank slate, and under the right conditions, they achieve superhuman performance. These algorithms are penalized when they make the wrong decisions and rewarded when they make the right ones – this is reinforcement.

Reinforcement learning solves the difficult problem of correlating immediate actions with the delayed returns they produce. Like humans, reinforcement learning algorithms sometimes have to wait a while to see the fruit of their decisions. They operate in a delayed return environment, where it can be difficult to understand which action leads to which outcome over many time steps.

It’s reasonable to assume that reinforcement learning algorithms will slowly perform better and better in more ambiguous, real-life environments while choosing from an arbitrary number of possible actions. That is, with time we expect them to be valuable to achieve goals in the real world.

Definitions

Reinforcement learning can be understood using the concepts of agents, environments, states, actions and rewards, all of which we’ll explain below. Capital letters tend to denote sets of things, and lower-case letters denote a specific instance of that thing.

- Agent: An agent takes actions. The algorithm is the agent.

- Actions (A): \(A\) is the set of all possible moves the agent can make. An action is almost self-explanatory, but it should be noted that agents usually choose from a list of discrete, possible actions.

- Discount factor: The discount factor is multiplied by future rewards as discovered by the agent in order to dampen these rewards’ effect on the agent’s choice of action. It is designed to make future rewards worth less than immediate rewards; i.e. it enforces a kind of short-term hedonism in the agent. Often expressed with the lower-case Greek letter gamma: \(\gamma\). If \(\gamma\) is \(0.8\), and there’s a reward of \(10\)points after \(3\) time steps, the present value of that reward is\(0.8^3 \times 10\). A discount factor of 1 would make future rewards worth just as much as immediate rewards.

- Environment: The world through which the agent moves, and which responds to the agent. The environment takes the agent’s current state and action as input, and returns as output the agent’s reward and its next state.

- State (\(S\)): A state is a concrete and immediate situation in which the agent finds itself. It can the current situation returned by the environment, or any future situation.

- Reward (\(R\)): A reward is the feedback by which we measure the success or failure of an agent’s actions in a given state. From any given state, an agent sends output in the form of actions to the environment, and the environment returns the agent’s new state (which resulted from acting on the previous state) as well as rewards, if there are any. Rewards can be immediate or delayed. They effectively evaluate the agent’s action.

- Policy (\(\pi\)): The policy is the strategy that the agent employs to determine the next action based on the current state. It maps states to actions, the actions that promise the highest reward.

- Value (\(V\)): The expected long-term return with discount, as opposed to the short-term reward \(R\). \(V\pi(s)\) is defined as the expected long-term return of the current state under policy \(\pi\). We discount rewards, or lower their estimated value, the further into the future they occur.

- Q-value or action-value (\(Q\)): Q-value is similar to Value, except that it takes an extra parameter, the current action \(a\). \(Q\pi(s, a)\) refers to the long-term return of an action taking action \(a\) under policy \(\pi\) from the current state \(s\). \(Q\) maps state-action pairs to rewards. Note the difference between Q and policy.

- Trajectory: A sequence of states and actions that influence those states.

Key distinctions

Reward is an immediate signal that is received in a given state, while value is the sum of all rewards you might anticipate from that state. Value is a long-term expectation, while reward is an immediate pleasure. They differ in their time horizons. This is why the value function, rather than immediate rewards, is what reinforcement learning seeks to predict and control.

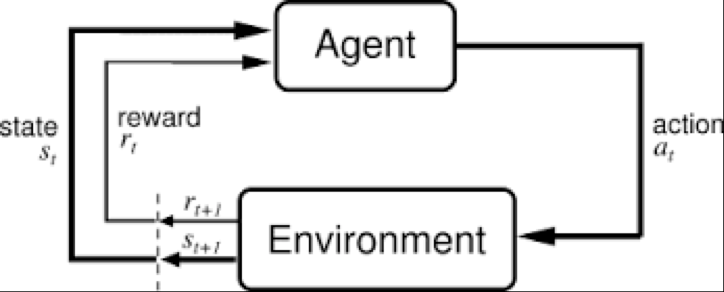

So environments are functions that transform an action taken in the current state into the next state and a reward; agents are functions that transform the new state and reward into the next action. We can know and set the agent’s function, but in most situations where it is useful and interesting to apply reinforcement learning, we do not know the function of the environment. It is a black box where we only see the inputs and outputs. Reinforcement learning represents an agent’s attempt to approximate the environment’s function, such that we can send actions into the black-box environment that maximize the rewards it spits out.

In the feedback loop above, the subscripts denote the time steps \(t\) and \(t+1\), each of which refer to different states: the state at moment \(t\), and the state at moment \(t+1\).

Reinforcement learning judges actions by the results they produce. It is goal oriented, and its aim is to learn sequences of actions that will lead an agent to achieve its goal, or maximize its objective function.

Here’s an example of an objective function for reinforcement learning; i.e. the way it defines its goal:

\[\sum_{t=0}^{t=\infty} \gamma^t r(x(t), a(t))\]We are summing reward function \(r\) over \(t\), which stands for time steps. So this objective function calculates all the reward we could obtain by running through. Here, \(x\) is the state at a given time step, and \(a\) is the action taken in that state. \(r\) is the reward function for \(x\) and \(a\).

Unlike other forms of machine learning – such as supervised and unsupervised learning – reinforcement learning can only be thought about sequentially in terms of state-action pairs that occur one after the other.

Reinforcement learning differs from both supervised and unsupervised learning by how it interprets inputs.

- Unsupervised learning: The algorithms learn similarities w/o names, and by extension they can spot the inverse and perform anomaly detection by recognizing what is unusual or dissimilar

- Supervised learning: These algorithms learn the correlations between data instances and their labels; that is, they require a labelled dataset. Those labels are used to “supervise” and correct the algorithm as it makes wrong guesses when predicting labels.

- Reinforcement learning: Actions based on short- and long-term rewards. Reinforcement learning can be thought of as supervised learning in an environment of sparse feedback.

Domain Selection

In fact, deciding which types of input and feedback your agent should pay attention to is a hard problem to solve. This is known as domain selection. Video games provide the sterile environment of the lab, where ideas about reinforcement learning can be tested. Domain selection requires human decisions, usually based on knowledge or theories about the problem to be solved; e.g. selecting the domain of input for an algorithm in a self-driving car might include choosing to include radar sensors in addition to cameras and GPS data.

State-Action Pairs & Complex Probability Distributions of Reward

The goal of reinforcement learning is to pick the best known action for any given state, which means the actions have to be ranked, and assigned values relative to one another.

Since those actions are state-dependent, what we are really gauging is the value of state-action pairs.

We map state-action pairs to the values we expect them to produce with the Q function, described above. The Q function takes as its input an agent’s state and action, and maps them to probable rewards. Reinforcement learning is the process of running the agent through sequences of state-action pairs, observing the rewards that result, and adapting the predictions of the Q function to those rewards until it accurately predicts the best path for the agent to take. That prediction is known as a policy.

Reinforcement learning is an attempt to model a complex probability distribution of rewards in relation to a very large number of state-action pairs. This is one reason reinforcement learning is paired with, say, a Markov decision process, a method to sample from a complex distribution to infer its properties.

Any statistical approach is essentially a confession of ignorance. The immense complexity of some phenomena (biological, political, sociological, or related to board games) make it impossible to reason from first principles. The only way to study them is through statistics, measuring superficial events and attempting to establish correlations between them, even when we do not understand the mechanism by which they relate. Reinforcement learning, like deep neural networks, is one such strategy, relying on sampling to extract information from data.

A reinforcement learning algorithm may tend to repeat actions that lead to reward and cease to test alternatives. There is a tension between the exploitation of known rewards, and continued exploration to discover new actions that also lead to victory. Reinforcement learning algorithms can be made to both exploit and explore to varying degrees, in order to ensure that they don’t pass over rewarding actions at the expense of known winners.

Reinforcement learning is iterative. In its most interesting applications, it doesn’t begin by knowing which rewards state-action pairs will produce. It learns those relations by running through states again and again, like athletes or musicians iterate through states in an attempt to improve their performance.

Neural Networks and Deep Reinforcement Learning

Neural networks are function approximators, which are particularly useful in reinforcement learning when the state space or action space are too large to be completely known.

A neural network can be used to approximate a value function, or a policy function. That is, neural nets can learn to map states to values, or state-action pairs to Q values. We can train a neural network on samples from the state or action space to learn to predict how valuable those are relative to our target in reinforcement learning.

Like all neural networks, they use coefficients to approximate the function relating inputs to outputs, and their learning consists to finding the right coefficients, or weights, by iteratively adjusting those weights along gradients that promise less error.

In reinforcement learning, convolutional networks can be used to recognize an agent’s state when the input is visual; That is, they perform their typical task of image recognition.

In reinforcement learning, given an image that represents a state, a convolutional net can rank the actions possible to perform in that state; for example, it might predict that running right will return 5 points, jumping 7, and running left none.

The above image illustrates what a policy agent does, mapping a state to the best action.

\[a=\pi(s)\]A policy maps a state to an action.

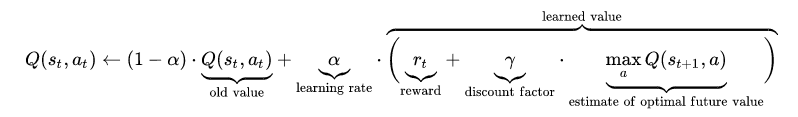

\(Q\) maps state-action pairs to the highest combination of immediate reward with all future rewards that might be harvested by later actions in the trajectory. Here is the equation for Q:

Having assigned values to the expected rewards, the Q function simply selects the state-action pair with the highest so-called Q value.

At the beginning of reinforcement learning, the neural network coefficients may be initialized stochastically. Using feedback from the environment, the neural net can use the difference between its expected reward and the ground-truth reward to adjust its weights and improve its interpretation of state-action pairs. This feedback loop is analogous to the backpropagation of error in supervised learning.

Reinforcement learning relies on the environment to send it a scalar number in response to each new action. The rewards returned by the environment can be varied, delayed or affected by unknown variables, introducing noise to the feedback loop. This leads us to a more complete expression of the Q function, which takes into account not only the immediate rewards produced by an action, but also the delayed rewards that may be returned several time steps deeper in the sequence.